0001764013false03-31FY2020.5.5.5P10YP5YP8Y00017640132020-04-012021-03-31iso4217:USD00017640132020-09-30xbrli:shares00017640132021-06-0100017640132021-03-3100017640132020-03-31iso4217:USDxbrli:shares0001764013us-gaap:SeriesAPreferredStockMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:SeriesAPreferredStockMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMember2019-04-012020-03-3100017640132019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:GeneralAndAdministrativeExpenseMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:GeneralAndAdministrativeExpenseMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:GeneralAndAdministrativeExpenseMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:GeneralAndAdministrativeExpenseMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-03-310001764013imvt:SubscriberMember2019-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2019-03-310001764013us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2019-03-310001764013us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2019-03-3100017640132019-03-310001764013imvt:SubscriberMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:PreferredStockMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:PreferredStockMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-03-310001764013imvt:SubscriberMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMemberimvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:SubscriberMemberimvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMemberus-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:UponAchievementOfEarnoutSharesMilestoneMemberus-gaap:PreferredStockMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMemberimvt:UponAchievementOfEarnoutSharesMilestoneMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:UponAchievementOfEarnoutSharesMilestoneMemberus-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:UponAchievementOfEarnoutSharesMilestoneMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:WarrantRedemptionMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:WarrantRedemptionMemberus-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:WarrantRedemptionMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:PreferredStockMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2021-03-310001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013imvt:WarrantRedemptionMember2019-04-012020-03-31imvt:segmentxbrli:pure0001764013imvt:SellersMemberimvt:ImmunovantSciencesLtdMember2019-12-170001764013imvt:ImmunovantSciencesLtdMember2019-12-180001764013imvt:ImmunovantSciencesLtdMember2019-12-182019-12-180001764013us-gaap:SeriesAPreferredStockMember2019-12-182019-12-180001764013imvt:ImmunovantSciencesLtdMembersrt:RestatementAdjustmentMember2019-12-18imvt:subleaseAgreement0001764013us-gaap:ConvertiblePreferredStockMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:ConvertiblePreferredStockMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:WarrantMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:WarrantMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013imvt:EarnoutSharesMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:EarnoutSharesMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:IPOMemberus-gaap:WarrantMember2019-05-3100017640132020-05-310001764013us-gaap:SeriesAPreferredStockMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-12-182019-12-1800017640132019-12-182019-12-180001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-12-182019-12-180001764013us-gaap:SeriesAPreferredStockMember2019-12-1800017640132019-12-180001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2018Member2019-12-180001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-12-18imvt:tradingDay0001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMemberimvt:MilestoneAchievementOneMember2023-03-310001764013srt:ScenarioForecastMemberimvt:MilestoneAchievementOneMember2023-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMemberimvt:MilestoneAchievementOneMember2025-03-310001764013srt:ScenarioForecastMemberimvt:MilestoneAchievementOneMember2025-03-310001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMemberimvt:ImmunovantSciencesLtdMember2021-03-310001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-03-3100017640132019-09-290001764013imvt:SponsorMember2019-09-292019-09-2900017640132020-09-172020-09-1700017640132017-12-192017-12-190001764013srt:MaximumMember2017-12-190001764013srt:MaximumMemberimvt:UponAchievementOfDevelopmentRegulatoryAndSalesMilestonesMember2017-12-1900017640132018-12-072018-12-070001764013imvt:AchievementOfDevelopmentAndRegulatoryMilestonesMember2019-05-312019-05-310001764013us-gaap:ServiceAgreementsMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:ServiceAgreementsMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013imvt:CapitalContributionsMemberus-gaap:ServiceAgreementsMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:ServiceAgreementsMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-06-300001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-08-310001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-09-012019-09-300001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-12-172019-12-170001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-07-310001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2019-07-012019-07-310001764013country:US2020-04-012021-03-310001764013country:US2019-04-012020-03-310001764013country:CH2020-04-012021-03-310001764013country:CH2019-04-012020-03-310001764013country:BM2020-04-012021-03-310001764013country:BM2019-04-012020-03-310001764013country:GB2020-04-012021-03-310001764013country:GB2019-04-012020-03-310001764013imvt:AllOtherCountriesMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013imvt:AllOtherCountriesMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013country:CH2021-03-310001764013country:GB2021-03-310001764013country:US2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:ResearchMembercountry:US2021-03-31imvt:promissoryNote0001764013imvt:RtwConvertiblePromissoryNotesMember2019-08-010001764013imvt:RtwConvertiblePromissoryNotesMember2019-09-260001764013imvt:BvfConvertiblePromissoryNotesMember2019-09-260001764013imvt:ConvertiblePromissoryNotesMember2019-12-170001764013imvt:ConvertiblePromissoryNotesMember2019-12-172019-12-170001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-12-172019-12-170001764013imvt:AccruedInterestMember2019-12-172019-12-170001764013us-gaap:SeriesAPreferredStockMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2021-03-310001764013imvt:FourSeriesAPreferredStockMemberMember2021-03-310001764013imvt:ThreeSeriesAPreferredStockMembersrt:MinimumMember2021-03-310001764013srt:MaximumMemberimvt:ThreeSeriesAPreferredStockMember2021-03-310001764013imvt:TwoSeriesAPreferredStockMembersrt:MinimumMember2021-03-310001764013srt:MaximumMemberimvt:TwoSeriesAPreferredStockMember2021-03-310001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-04-012020-04-300001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-04-012020-04-300001764013us-gaap:OverAllotmentOptionMember2020-04-012020-04-300001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-04-300001764013us-gaap:CommonStockMemberimvt:ImmunovantSciencesLtdMember2020-09-300001764013imvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-09-300001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-09-012020-09-300001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-09-012020-09-300001764013us-gaap:OverAllotmentOptionMember2020-09-012020-09-300001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2020-09-3000017640132021-01-012021-01-310001764013imvt:UnderwrittenPublicOfferingMember2021-01-012021-01-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2020-03-310001764013us-gaap:IPOMember2019-05-310001764013us-gaap:IPOMember2020-05-140001764013us-gaap:IPOMember2020-05-142020-05-1400017640132020-05-012020-05-310001764013us-gaap:PrivatePlacementMember2019-05-312019-05-310001764013us-gaap:PrivatePlacementMembersrt:MinimumMember2019-05-310001764013us-gaap:PrivatePlacementMember2019-05-310001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2019Member2019-12-310001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2019Member2019-12-012019-12-310001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2019Memberus-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2019-12-012019-12-3100017640132020-04-010001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2019Member2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberimvt:EquityIncentivePlan2019Member2021-03-310001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2018Member2018-09-300001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2018Member2019-07-310001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2018Member2021-03-310001764013imvt:EquityIncentivePlan2019Member2020-03-310001764013srt:MinimumMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013srt:MaximumMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013srt:MinimumMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013srt:MaximumMember2019-04-012020-03-310001764013us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2021-03-310001764013us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2020-04-012021-03-310001764013us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberimvt:RoivantSciencesLtdMember2021-03-3100017640132020-06-30

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

_____________________

FORM 10-K

_____________________

(Mark One)

| | | | | |

☒ | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2021

OR

| | | | | |

| ☐ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

Commission File Number: 001-38906

_____________________

IMMUNOVANT, INC.

(Exact name of Registrant as specified in its Charter)

_____________________

| | | | | | | | |

| Delaware | | 83-2771572 |

(State or other jurisdiction of

incorporation or organization) | | (I.R.S. Employer

Identification No.) |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| 320 West 37th Street | 10018 |

| New York, | NY |

| (Address of principal executive offices) | (Zip Code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (917) 580-3099

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Title of each class | | Trading

Symbol(s) | | Name of each exchange

on which registered |

| Common Stock, $0.0001 par value per share | | IMVT | | The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC |

Securities registered pursuant to section 12(g) of the Act: None.

_____________________

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Large accelerated filer | ☒ | | Accelerated filer | ☐ |

| | | | |

| Non-accelerated filer | ☐ | | Smaller reporting company | ☒ |

| | | | |

| | | Emerging growth company | ☐ |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the Registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☐ No ☒

The aggregate market value of the registrant’s common stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant, based on the closing price of the registrant’s common stock on The Nasdaq Global Select Market as of September 30, 2020, the last business day of the registrant’s most recently completed second fiscal quarter, was approximately $1,460.5 million, based on the closing price of the registrant’s common stock on The Nasdaq Global Select Market of $35.19 per share.

As of June 1, 2021, the Registrant had 97,976,695 shares of common stock, $0.0001 par value per share, outstanding.

IMMUNOVANT, INC.

ANNUAL REPORT ON FORM 10-K

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CAUTIONARY NOTE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2021 (this “Annual Report”) contains forward-looking statements that involve substantial risks and uncertainties. In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by the words “anticipate,” “believe,” “continue,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “forecast,” “goal,” “hope,” “intend,” “may,” “might,” “objective,” “ongoing,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “should,” “target,” “will” and “would,” or the negative of these terms, or other comparable terminology intended to identify statements about the future. These statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors that may cause our actual results, levels of activity, performance or achievements to be materially different from the information expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. Although we believe that we have a reasonable basis for each forward-looking statement contained in this Annual Report, we caution you that these statements are based on a combination of facts and factors currently known by us and our expectations of the future, about which we cannot be certain. Forward-looking statements include statements about:

•the timing, progress, costs and results of our clinical trials for IMVT-1401;

•potential benefit risk in current and future indications and the ability to achieve regulatory approval in licensed jurisdictions;

•future operating or financial results;

•future acquisitions, business strategy and expected capital spending;

•the timing of meetings with and feedback from regulatory authorities as well as any submission of filings for regulatory approval of IMVT-1401;

•the potential advantages and differentiated profile of IMVT-1401 compared to existing therapies for the applicable indications;

•our ability to successfully manufacture or have manufactured drug product for clinical trials and commercialization;

•our ability to successfully commercialize IMVT-1401, if approved;

•the rate and degree of market acceptance of IMVT-1401, if approved;

•the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on our business, operations and supply chain, including the potential impact on our clinical trial plans and timelines, such as the enrollment, activation and initiation of additional clinical trial sites, and the results of our clinical trials;

•our expectations regarding the size of the patient populations for and opportunity for and clinical utility of IMVT-1401, if approved for commercial use;

•our estimates of our expenses, ongoing losses, future revenue, capital requirements and needs for or ability to obtain future financing to complete the clinical trials for and commercialize IMVT-1401;

•our dependence on and plans to leverage third parties for research and development, clinical trials, manufacturing, and other activities;

•our ability to maintain intellectual property protection for IMVT-1401;

•our ability to identify, acquire or in-license and develop new product candidates;

•our ability to identify, recruit and retain key personnel;

•developments and projections relating to our competitors or industry; and

•future payments of dividends and the availability of cash for payment of dividends.

You should refer to “Item 1A. Risk Factors” and elsewhere in this document for a discussion of important factors that may cause our actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied by our forward-looking statements. As a result of these factors, we cannot assure you that the forward-looking statements in this Annual Report will prove to be accurate. Furthermore, if our forward-looking statements prove to be inaccurate, the inaccuracy may be material.

In light of the significant uncertainties in these forward-looking statements, you should not regard these statements as a representation or warranty by us or any other person that we will achieve our objectives and plans in any specified time frame, or at all.

In addition, statements that “we believe” and similar statements reflect our beliefs and opinions on the relevant subject. These statements are based upon information available to us as of the date of this Annual Report, and while we believe such information forms a reasonable basis for such statements, such information may be limited or incomplete, and our statements should not be read to indicate that we have conducted an exhaustive inquiry into, or review of, all potentially available relevant information.

We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as required by law. We qualify all of our forward-looking statements by these cautionary statements.

Investors and others should note that we may announce material business and financial information to our investors using our investor relations website (www.immunovant.com), SEC filings, webcasts, press releases, and conference calls. We use these mediums, including our website, to communicate with our stockholders and the public about our company, our product candidates, and other matters. It is possible that the information that we make available may be deemed to be material information. We therefore encourage investors and others interested in our company to review the information that we make available on our website.

Unless the context otherwise indicates, references in this report to the terms “Immunovant,” “the Company,” “we,” “our” and “us” refer to Immunovant, Inc. and its wholly owned subsidiaries. Prior to December 18, 2019, we were known as Health Sciences Acquisitions Corporation (“HSAC”). On December 18, 2019, HSAC completed the acquisition of 100% of the outstanding shares of Immunovant Sciences Ltd. (“ISL”), which we refer to as the “Business Combination.” References herein to “we,” “our” and “us” may refer, as context requires, to ISL and its wholly owned subsidiaries prior to the Business Combination.

SUMMARY RISK FACTORS

You should consider carefully the risks described under “Risk Factors” in Part I, Item 1A of this Annual Report on Form 10-K. References to “we,” “us,” and “our” in this section titled “Summary Risk Factors” refer to Immunovant, Inc. and its wholly owned subsidiaries. A summary of the risks that could materially and adversely affect our business, financial condition, operating results and prospects include the following:

•Our success relies upon a singular product candidate, IMVT-1401, for which all clinical development by the Company has paused due to its presumed causation of elevated lipid levels in patients dosed with the drug. Unless we can determine a dosing regimen, target patient population, safety monitoring and risk management for IMVT-1401 in autoimmune diseases for which the risks of lipid elevations and albumin reductions can be mitigated, we will not be able to show adequate benefit to risk ratio and will not be able to continue clinical development or seek or obtain marketing authorization in any jurisdiction.

•Our product candidate has caused and may cause adverse events (including but not limited to, elevated total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (“LDL”) levels and reductions in albumin) or have other properties that could delay or prevent its regulatory approval, cause us to further suspend or discontinue clinical trials, abandon further development or limit the scope of any approved label or market acceptance.

•Clinical trials are very expensive, time-consuming, difficult to design and implement, and involve uncertain outcomes.

•Enrollment and retention of patients in clinical trials is an expensive and time-consuming process and could be made more difficult or rendered impossible by multiple factors outside our control.

•The results of our nonclinical and clinical trials may not support our proposed claims for our product candidate, or regulatory approval on a timely basis or at all, and the results of earlier studies and trials may not be predictive of future trial results.

•Interim, “top-line” or preliminary data from our clinical trials that we announce or publish from time to time may change as more patient data become available and are subject to audit and verification procedures that could result in material changes in the final data.

•Our business is heavily dependent on the successful development, regulatory approval and commercialization of our sole product candidate, IMVT-1401.

•We may not be able to successfully develop and commercialize our product candidate IMVT-1401 on a timely basis or at all.

•Our business, operations and clinical development plans and timelines and supply chain could be adversely affected by the effects of health epidemics, including the ongoing global Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019, or the COVID-19 pandemic, on the manufacturing, clinical trials and other business activities performed by us or by third parties with whom we conduct business, including our contract manufacturers, contract research organizations, or CROs, shippers and others.

•We expect to incur significant losses for the foreseeable future and may never achieve or maintain profitability.

•RSL owns a significant percentage of shares of our common stock and may exert significant control over matters subject to stockholder approval.

•Our failure to maintain or continuously improve our quality management program could have an adverse effect upon our business, subject us to regulatory actions, cause a loss of patient confidence in us or our products, among other negative consequences.

•We are reliant on third parties to conduct, supervise and monitor our clinical trials, and if those third parties perform in an unsatisfactory manner or fail to comply with applicable requirements, or our quality management program fails to detect such events in a timely manner, it may harm our business.

•Our third-party manufacturers may encounter difficulties in production, or our quality management program fails to detect quality issues at our third-party manufacturers, that may delay or prevent our ability to obtain marketing approval or commercialize our product candidates, after approval.

•We have a limited operating history and have never generated any product revenue.

•We will require additional capital to fund our operations, and if we fail to obtain necessary financing, we may not be able to complete the development and commercialization of IMVT-1401.

•Raising additional funds by issuing equity securities may cause dilution to existing stockholders, raising additional funds through debt financings may involve restrictive covenants, and raising funds through lending and licensing arrangements may restrict our operations or require us to relinquish proprietary rights.

•We rely on the license agreement with HanAll Biopharma Co., Ltd., or the HanAll Agreement, to provide rights to the core intellectual property relating to IMVT-1401. Any termination or loss of significant rights under the HanAll Agreement would adversely affect our development or commercialization of IMVT-1401.

•The HanAll Agreement obligates us to make certain milestone payments, some of which may be triggered prior to our potential commercialization of IMVT-1401.

•We may not be able to manage our business effectively if we are unable to attract and retain key personnel.

•We plan to expand our organization, and we may experience difficulties in managing this growth, which could disrupt our operations.

•We face significant competition from other biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies targeting autoimmune disease indications, and our operating results will suffer if we fail to compete effectively.

•We are subject to stringent and changing privacy and data security laws, contractual obligations, self-regulatory schemes, government regulation, and standards related to data privacy and security. Further, if our security measures are compromised now, or in the future, or the security, confidentiality, integrity or availability of, our information technology, software, services, communications or data is compromised, limited or fails, this could result in a material adverse effect on our business.

PART I

Item 1. Business

Overview

We are a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on enabling normal lives for people with autoimmune diseases. We are developing a novel, fully human monoclonal antibody, IMVT-1401 (formerly referred to as RVT-1401), that selectively binds to and inhibits the neonatal fragment crystallizable receptor (“FcRn”). IMVT-1401 is the product of a multi-step, multi-year research program conducted by HanAll Biopharma Co., Ltd. (“HanAll”) to design a highly potent anti-FcRn antibody optimized for subcutaneous delivery. We obtained rights to IMVT-1401 pursuant to our license agreement (the “HanAll Agreement”) with HanAll. Pursuant to the HanAll Agreement, we will be responsible for future contingent payments and royalties, including up to an aggregate of $442.5 million upon the achievement of certain development, regulatory and sales milestone events. We are also obligated to pay HanAll tiered royalties ranging from the mid-single digits to mid-teens on net sales of licensed products, subject to standard offsets and reductions as set forth in the HanAll Agreement.

Our product candidate has been dosed in small volumes (e.g., 2 mL) and with a 27-gauge needle, while still generating therapeutically relevant pharmacodynamic activity, important attributes that we believe will drive patient preference and market adoption. In nonclinical studies and in clinical trials conducted to date, IMVT-1401 has been observed to reduce immunoglobulin G (“IgG”) antibody levels. High levels of pathogenic IgG antibodies drive a variety of autoimmune diseases and, as a result, we believe IMVT-1401 has the potential for broad application in these disease areas. We intend to develop IMVT-1401 in autoimmune diseases for which there is robust evidence that pathogenic IgG antibodies drive disease manifestation and for which reduction of IgG antibodies should lead to clinical benefit.

Autoimmune diseases are conditions where an immune response is inappropriately directed against the body’s own healthy cells and tissues. According to a 2012 study by the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association, approximately 50 million people in the United States suffer from one of more than 100 diagnosed autoimmune diseases. Predisposing factors may include genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers and other factors not yet known. Many of these diseases are associated with high levels of pathogenic IgG antibodies, which are the most abundant type of antibody produced by the human immune system, accounting for approximately 75% of antibodies in the plasma of healthy people. IgG antibodies are important in the defense against pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria. In many autoimmune diseases, IgG antibodies inappropriately develop against normal proteins found in the body, directing the immune system to attack specific organs or organ systems.

Unfortunately, safe and effective treatment options for patients suffering from autoimmune diseases are lacking. Currently available treatments are generally limited to corticosteroids and immunosuppressants in early-stage disease and intravenous immunoglobulin (“IVIg”) or plasma exchange in later-stage disease. These approaches often fail to address patients’ needs since they are limited by delayed onset of action, waning therapeutic benefit over time and unfavorable safety profiles.

FcRn plays a pivotal role in preventing the degradation of IgG antibodies. The physiologic function of FcRn is to modulate the catabolism of IgG antibodies, and inhibition of FcRn, such as through use of an anti-FcRn antibody, has been shown to reduce levels of pathogenic IgG antibodies. Completed clinical trials of Immunovant and other anti-FcRn antibodies in IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases have generated promising results, suggesting that FcRn is a therapeutically important pharmacologic target to reduce levels of these disease-causing IgG antibodies.

In several nonclinical studies and a multi-part Phase 1 clinical trial in healthy volunteers, intravenous and subcutaneous delivery of IMVT-1401 demonstrated dose-dependent IgG antibody reductions and was observed to be generally well tolerated. In the highest dose cohort from the multiple-ascending dose portion of the Phase 1 clinical trial, four weekly subcutaneous administrations of 680 mg resulted in a mean maximum reduction of serum IgG levels of 78%, with a standard deviation of 2%. IMVT-1401 was generally well-tolerated in this study and the majority of adverse events reported were mild or moderate; as previously disclosed, lipid levels were not measured contemporaneously during these Phase 1 clinical trials of IMVT-1401. Injection site reactions were similar between IMVT-1401 and placebo arms.

We are developing IMVT-1401 as a fixed-dose, self-administered subcutaneous injection on a convenient weekly, or less frequent, dosing schedule as discussed below. As a result of our rational design, we believe that IMVT-1401, if developed and approved for commercial sale, would be differentiated from currently available, more invasive treatments for advanced IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases, (e.g., Myasthenia Gravis (“MG”), Thyroid Eye Disease (“TED”, formerly referred to as Graves’ Ophthalmopathy, or “GO”), Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (“WAIHA”), Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura, Pemphigus Vulgaris, Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy, Bullous Pemphigoid, Neuromyelitis Optica, Pemphigus Foliaceus, Guillain-Barré Syndrome and PLA2R+ Membranous Nephropathy). In 2020, these diseases had an aggregate prevalence of approximately 278,000 patients in the United States and 480,000 patients in Europe.

The estimated prevalence of certain IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases are set forth in the following table: | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Estimated Prevalence (2020) |

| Indication | U.S. | | Europe* |

| Myasthenia Gravis | 66,000 | | | 104,000 | |

| Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia | 42,000 | | | 67,000 | |

| Thyroid Eye Disease | 33,000 | | | 52,000 | |

| Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura | 65,000 | | | 140,000 | |

| Pemphigus Vulgaris | 28,000 | | | 45,000 | |

| Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy | 16,000 | | | 25,000 | |

| Bullous Pemphigoid | 8,000 | | | 13,000 | |

| Neuromyelitis Optica | 7,000 | | | 12,000 | |

| Pemphigus Foliaceus | 7,000 | | | 11,000 | |

| Guillain-Barré Syndrome | 4,000 | | | 7,000 | |

| PLA2R+ Membranous Nephropathy | 2,000 | | | 4,000 | |

| Total | 278,000 | | | 480,000 | |

_______________ *Europe includes all E.U. countries, the U.K. and Switzerland

To the extent we choose to develop IMVT-1401 for certain of these rare diseases, we plan to seek orphan drug designation in the United States and Europe, where applicable. Such designations would primarily provide financial and exclusivity incentives intended to make the development of orphan drugs financially viable. However, we have not yet obtained such designation for any of our target indications, and there is no certainty that we will obtain such designation, or maintain the benefits associated with such designation if we do obtain it.

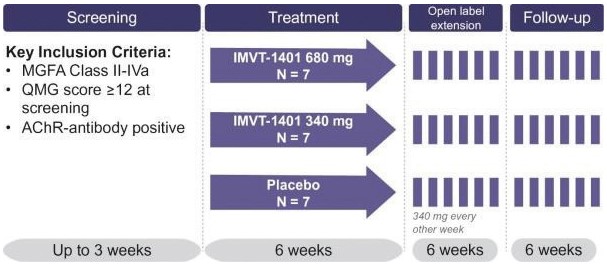

We are developing IMVT-1401 as a fixed-dose subcutaneous injection, and have focused our initial development efforts on the treatment of MG, WAIHA and TED. We are also pursuing a series of other indications. MG is an autoimmune disease associated with muscle weakness with an estimated prevalence of one in 5,000, with up to 66,000 cases in the United States. In MG, patients develop pathogenic IgG antibodies that attack critical signaling proteins at the junction between nerve and muscle cells. The majority of MG patients suffer from progressive muscle weakness, with maximum weakness occurring within six months of disease onset in most patients. In severe cases, MG patients can experience myasthenic crisis, in which respiratory function is weakened to the point where it becomes life-threatening, requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. In August 2020, we reported top-line results from an interim analysis of 15 participants in our ASCEND MG trial, a multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 2a clinical trial designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics and efficacy of IMVT-1401 in patients with moderate-to-severe MG. After the interim analysis, two additional participants enrolled and were randomized. The trial is now completed. See “IMVT-1401 for the Treatment of Myasthenia Gravis” below for further discussion.

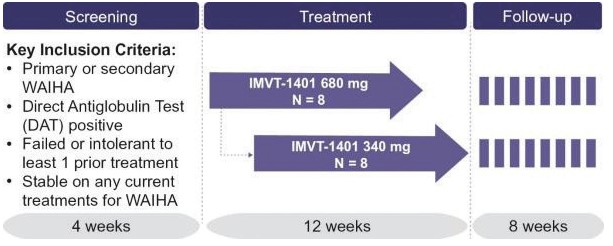

WAIHA is a rare hematologic disease in which autoantibodies mediate hemolysis, or the destruction of red blood cells (“RBCs”). Based on published estimates, we believe that there are approximately 42,000 patients in the United States and 67,000 patients in Europe living with WAIHA. The clinical presentation is variable and most commonly includes symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue, weakness, skin paleness and shortness of breath. In severe cases, hemoglobin levels are unable to meet the body’s oxygen demand, which can lead to heart attacks, heart failure and even death. In August 2020, we initiated dosing for ASCEND WAIHA, our Phase 2, open-label, sequential, two cohort clinical trial in patients with WAIHA. In February 2021, we voluntarily paused dosing in our clinical trials for IMVT-1401. Because the ASCEND WAIHA trial is an open label trial, the pause did not necessitate study termination but rather a suspension. See “Recent Developments in Our Clinical Programs” below for further discussion.

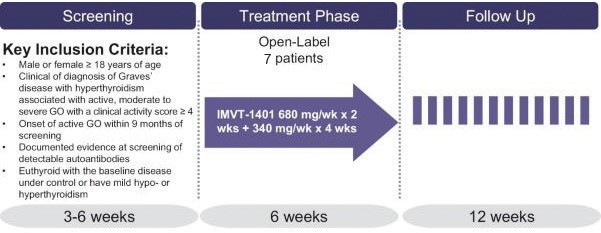

TED is an autoimmune inflammatory disorder that affects the muscles and other tissues around the eyes, which can be sight-threatening. TED has an estimated annual incidence of 16 in 100,000 women and 2.9 in 100,000 men in North America and Europe. Initial symptoms may include a dry and gritty ocular sensation, sensitivity to light, excessive tearing, double vision and a sensation of pressure behind the eyes. In March 2020, we announced initial results from our ASCEND GO-1 trial, a Phase 2a open-label single-arm clinical trial in Canada in seven patients with TED. This trial is now completed. In October 2019, we initiated dosing in our ASCEND GO-2 trial, a randomized, masked, placebo-controlled Phase 2b clinical trial in patients with moderate-to-severe active TED with confirmed autoantibodies to thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (“TSHR”). In February 2021, we voluntarily paused dosing in our clinical trials for IMVT-1401. Because the pause led to unblinding ASCEND GO-2, this trial was terminated after the last patient completed the withdrawal visit and the follow-up visit. See “Recent Developments in Our Clinical Programs” below for further discussion.

Recent Developments in Our Clinical Programs

In February 2021, we voluntarily paused dosing in our clinical trials for IMVT-1401 due to elevated total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (“LDL”) levels observed in some trial subjects treated with IMVT-1401. We have informed regulatory authorities and trial subjects and investigators of this voluntary pause of dosing in our studies that were ongoing at that time, ASCEND GO-2, our Phase 2b trial in Thyroid Eye Disease and ASCEND WAIHA, our Phase 2 trial in Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia.

Program-wide Review

In order to better characterize the observed lipid findings, we conducted from February 2021 through May 2021 a program-wide data review (including both clinical and nonclinical data) with input from external scientific and medical experts.

In our ASCEND GO-2 trial, lipid parameters were assessed at baseline, at week 12, and at week 20 following eight weeks off drug. Based on preliminary, unblinded data, median LDL cholesterol at week 12 was increased by approximately 12 mg/dL in the 255 mg dose group (corresponding to an increase from baseline of approximately 15%), by approximately 33 mg/dL in the 340 mg dose group (corresponding to an increase from baseline of approximately 37%), by approximately 62 mg/dL in the 680 mg dose group (corresponding to an increase from baseline of approximately 52%) and did not increase in the control group. The data analysis indicates a dose-dependent increase in lipids. Average high-density lipoprotein (“HDL”) and triglyceride levels also increased but to a much lesser degree. We also observed correlated decreases in albumin levels and the rate and extent of albumin reductions were dose-dependent. Subjects receiving the 255 mg weekly dose (“QW”) experienced the smallest reductions in albumin through week 12, with a median reduction of about 16% from baseline, while subjects receiving the 340 mg or 680 mg QW dose experienced median reductions of albumin of 26% or 40%, respectively. At week 20, both lipids and albumin returned to baseline.

In our open label ASCEND WAIHA trial, only two subjects completed 12 weeks of dosing prior to the program-wide pause in dosing, with three additional subjects partially completing the dosing period. Pre-specified and post-hoc lipid test results from these five subjects were analyzed along with post-hoc lipid test results performed on frozen samples from ASCEND MG subjects (where available) and post-hoc lipid test results from our Phase 1 Injection Site study. LDL elevations observed in the ASCEND WAIHA and ASCEND MG subject populations and in healthy subjects in the Phase 1 Injection Site Study also appeared to be dose-dependent and were generally consistent in magnitude with the elevations observed in ASCEND GO-2 subjects.

No major adverse cardiovascular events have been reported to date in IMVT-1401 clinical trials.

Integrated Safety Assessment and Regulatory Interactions

It is our intent to resume development across multiple indications for IMVT-1401. We are in the process of drafting multiple study protocols and updating our program-wide safety strategy for discussions with regulatory agencies. The elements of our development program will include extensive pharmacokinetic ("PK") and pharmacodynamic ("PD") modeling to select dosing regimens for IMVT-1401 which optimize reductions in total IgG levels while minimizing the impact on albumin and LDL levels, particularly for clinical studies containing long-term treatment extensions. These protocols will likely include protocol-directed guidelines for the management of any observed lipid abnormalities. While increases in LDL over an 8 to 12 week treatment duration would not be expected to pose a safety concern for patients, the risk-benefit profile of long-term administration of IMVT-1401 will need to incorporate any unfavorable effects on lipid profiles. Discussions with regulatory agencies, including the FDA, are expected to commence during the second half of the calendar year 2021.

Current Status of Our Clinical Trials

•Myasthenia Gravis: In August 2020, we reported top-line results from an interim analysis of 15 participants in our ASCEND MG trial, a multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 2a clinical trial designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics and efficacy of IMVT-1401 in patients with moderate-to-severe MG. After the interim analysis, two additional participants enrolled and were randomized. The trial is now completed. Before the voluntary pause of dosing, we had a favorable end of Phase 2 meeting with the FDA on the design of our Phase 3 registrational program in MG and we were planning on advancing our clinical trials for this indication. Based on our integrated safety analysis, we plan to meet with the FDA to propose further development to evaluate additional dosing levels and regimens as well as to include additional safety monitoring and considerations such as lipid and albumin monitoring and incorporating an independent safety monitoring committee. Contingent upon FDA feedback, we plan to initiate a pivotal study in MG late in the calendar year 2021 or early part of the calendar year 2022.

•Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: Our ASCEND WAIHA trial is an open label trial and we are planning on advancing our clinical trials for this indication. During the fall of 2021, we plan to commence discussions with the FDA on re-initiating this study, incorporating additional safety considerations and risk management as well as additional dosing regimens. We anticipate re-initiating this study based on a favorable outcome from these meetings late in the calendar year 2021 or early part of the calendar year 2022.

•Thyroid Eye Disease: Our voluntary pause in dosing led to unblinding of the ASCEND GO-2 trial and this trial was terminated after the last patient completed the withdrawal visit and the follow-up visit. Treatment with IMVT-1401 reduced both IgG and disease specific pathogenic IgG over the 12-week treatment period. However, the efficacy results, based on approximately half the anticipated number of subjects who had reached the week 13 primary efficacy analysis at the time of the termination of the trial, were inconclusive. The primary endpoint of the proportion of proptosis responders was not met, and although not tested statistically, post hoc evaluation of other endpoints measured (Clinical Activity Score ("CAS") and diplopia scores) indicated the desired magnitude of treatment effect likely would not have been achieved. However, levels of IgG were reduced across IMVT-1401 dosing groups, and analysis of the receptor occupancy data suggest binding of IMVT-1401 to the Fc receptor. Additional exploratory work on other disease biomarkers is under evaluation. Further discussions with external experts are ongoing to determine whether a specific population can be identified to optimize the clinical performance of IMVT-1401. Based on these analyses, we are likely to design another Phase 2 trial in TED or another thyroid-related disease as our next study in this therapeutic area and initiate discussions with regulatory authorities before the end of the calendar year 2021.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodynamics (PD)

The PK and PD (including serum concentrations of total IgG, albumin, and lipids) of IMVT-1401 were evaluated in healthy subjects in our Phase 1 clinical trial and Phase 1 Injection Site Study, and in patients with MG, TED and WAIHA in our ASCEND MG, ASCEND GO-1, ASCEND GO-2 and ASCEND WAIHA trials. Over the course of development, we have made significant progress in understanding the PK profiles, PD responses, and PK/PD relationships for IMVT-1401. In addition, we have established preliminary population PK and population PK/PD models using pooled data from all clinical studies to better understand and predict the PK and PD properties associated with various treatment regimens across different populations.

To date, single doses of IMVT-1401 ranged from 100 mg to 1530 mg IV and 1.5 mg/kg to 765 mg and were administered by subcutaneous injections (“SC”) to healthy subjects. Multiple doses of 255 mg, 340 mg, and 680 mg SC QW have been studied in healthy subjects (up to 4 weeks of dosing) and patients with TED, MG, or WAIHA (up to 12 weeks of dosing). Based on preliminary data from our ASCEND GO-2 trial in TED, drug concentrations achieved after 680 mg SC QW resided predominantly in the linear elimination phase of the PK profile and were estimated to maintain target saturation during the dosing intervals in most subjects. The mean maximal reduction of total IgG achieved with maximal target engagement was approximately 80% and was achieved after 7 weeks of dosing. Drug concentrations achieved with 255 mg or 340 mg SC QW did not maintain target saturation throughout the dosing intervals in the majority of subjects; total IgG levels continued to decrease and were reduced by median Emax of approximately 62% and 69%, respectively, at the end of the 12-week dosing period. The shoulder region of the dose-response curve for reduction in total IgG was covered and observed. Within the dose range studied, the rate and extent of albumin reductions and lipid elevations were dose-dependent across different populations. Over a 12-week dosing period, median Emax of albumin reductions were approximately 16%, 26%, 40% and median increases in LDL were approximately 15%, 37% and 52% for the 255 mg, 340 mg and 680 mg SC QW doses, respectively. The lipid elevations were highly correlated with albumin reductions. Unlike the PK/PD relationship for total IgG, the shoulder region of the dose-response curves for reduction in albumin and increases in LDL were not clearly observed. Total IgG, albumin, and lipids levels returned to baseline within eight weeks after the last dose of a 12-week treatment.

Comprehensive understanding of the PK and PD characteristics of IMVT-1401 has enabled creation of robust mathematical models to support the selection of future dosing regimens. The discordance between the PK/PD response relationship for IgG and that of albumin or LDL suggests options for dosing regimens that provide potentially effective reductions in total IgG (and pathologic autoantibodies) while minimizing effects on albumin and LDL levels. Optimized dosing regimens, if shown to be effective, could improve the risk/benefit profile of IMVT-1401 while the ease of administration of our current formulation could enhance the overall patient experience.

Potential New Indications

We continue to evaluate potential new indications for IMVT-1401 by considering a number of factors including, but not limited to, degree of unmet need, degree of potential benefit offered by the treatment, safety-related parameters, target patient population size, likely duration of dosing and commercial potential.

We have identified many attractive first-in-class indications with high unmet need and scientific rationale for anti-FcRn therapy. In our studies to date, we learned that IMVT-1401 has the potential to be more effective than we expected at providing therapeutic relief for patients across a broad range of indications. We also believe that certain indications with existing anti-FcRn programs also offer a significant opportunity to provide unique patient benefit and therefore a strong commercial opportunity. Accordingly, we plan to announce two new indications and submit INDs and our trial designs to the FDA over the next 12 months. For competitive reasons, we will likely announce these indications only after we have agreement with the FDA that we may proceed with a planned protocol. We believe that one or two of these new indications will involve a new phase 2 program whereas one of our new indications can begin with a pivotal study in 2022.

Business Strategy

Our goal is to become a leading biopharmaceutical company in the development and commercialization of innovative therapies for autoimmune diseases with significant unmet need. To execute our strategy, we plan to:

•Maximize the probability of success of IMVT-1401. We plan to leverage IMVT-1401’s differentiated profile in target indications where the anti-FcRn mechanism has already established clinical proof-of-concept. We intend to identify and target a variety of IgG-mediated autoimmune indications based on the following factors:

◦Insufficient benefit of the standard of care;

◦Disease severity that warrants novel therapies;

◦Ability to rapidly establish proof-of-concept through comparatively short duration clinical trials using validated clinical endpoints; and

◦Ability to rapidly initiate pivotal trial programs and potentially receive regulatory approval.

•Broad, portfolio-level criteria for the selection of new indications. We are including not only new indications that could enhance our speed to market such as chronic indications with high unmet need and less competition, but also indications requiring shorter-term dosing, and indications where we can take advantage of data and momentum achieved through our studies in MG, WAIHA and TED.

•Rapidly advance development of IMVT-1401 for the treatment of MG and WAIHA. We are currently developing IMVT-1401 for the treatment of MG and WAIHA by leveraging the strong biologic rationale of targeting FcRn to reduce IgG antibody levels and the clinical and regulatory insights gained from other FcRn-targeted therapies in MG. We also recognize the need to quickly explore subpopulations in TED to determine if the clinical performance of IMVT-1401 can be optimized in this indication.

•Identify and acquire or in-license additional innovative therapies for autoimmune diseases. Our controlling stockholder, Roivant Sciences Ltd. (“RSL”), and its subsidiaries, have a track record of acquiring or in-licensing products in a range of therapeutic areas. We will continue to partner and collaborate with RSL in identifying and evaluating potential acquisition and in-licensing opportunities in support of our goal to develop and commercialize innovative therapies for autoimmune diseases with significant unmet need.

IMVT-1401

Overview

IMVT-1401 (formerly referred to as RVT-1401) is a novel, fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to and inhibits FcRn. In our Phase 1 clinical trial, IMVT-1401 has demonstrated dose-dependent reductions in serum levels of IgG antibodies and was generally well-tolerated following subcutaneous and intravenous administration to healthy volunteers. In addition, completed clinical trials of other anti-FcRn antibodies have produced positive proof-of-concept activity in multiple IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases. We believe that these data support FcRn as a viable pharmacologic target with the potential to address multiple IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases. We intend to develop IMVT-1401 as a fixed-dose, self-administered subcutaneous injection on a convenient weekly, or less frequent, dosing schedule.

IMVT-1401 has been assigned the nonproprietary name batoclimab on the World Health Organization’s Recommended International Nonproprietary Names List.

Generation of IMVT-1401 and In Vitro Properties

IMVT-1401 is the result of a multi-step, multi-year research program conducted by our partner, HanAll, to engineer an antibody with the potency, specificity, safety, and pharmacokinetic properties optimized for subcutaneous administration. The selection of initial candidates was the result of screening a library of nearly 10,000 antibodies generated from both transgenic animal systems as well as phage-display libraries. These initial candidates were prioritized based on:

•Potency and specificity for FcRn;

•Ability to block the IgG-FcRn interaction;

•Ability to remain bound to FcRn regardless of pH;

•High production and stability in standard antibody production cell lines;

•Ability to achieve high concentrations appropriate for subcutaneous delivery; and

•Potential lack of immunogenicity.

IMVT-1401 was generated using the OmniAb transgenic rat platform from Open Monoclonal Technology (“OMT”). OMT was later acquired by Ligand Pharmaceuticals in 2015.

IMVT-1401 has been engineered to express specific known mutations that eliminate effector function. Traditional antibodies contain amino acid sequences that can trigger antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (“ADCC”) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (“CDC”) in which bound antibodies are recognized by effector components of the immune system which leads to inflammation. While this is an important mechanism for elimination of pathogens, triggering ADCC or CDC can lead to unintended immune activation and side effects. For this reason, IMVT-1401 was engineered with specific and validated mutations known to reduce ADCC and CDC.

Potential Benefits of IMVT-1401

As a result of the rational design of IMVT-1401, we believe that IMVT-1401, if approved for use, could provide the following benefits:

•Subcutaneous delivery. Based on PK/PD and clinical data, we believe that we will be able to obtain therapeutically relevant levels of IgG reduction using 2-mL or lesser volume subcutaneous injections. Our current formulation is concentrated at 170 mg/mL.

•Simple dosing schedule. We are developing IMVT-1401 as a fixed-dose subcutaneously administered regimen without the need for preceding intravenous induction doses or lengthy subcutaneous infusions. If approved, we intend to market IMVT-1401 as a fixed-dose pre-filled syringe or auto-injector, which would allow for convenient self-administration, eliminating the need for frequent and costly clinic visits, and reduce complexity and errors associated with calculating individual doses.

•Low immunogenicity risk. IMVT-1401 is a fully human monoclonal antibody, and therefore contains only amino acid sequences native to humans, hypothesizing a lower risk of immunogenicity development.

•Low effector function. IMVT-1401 has been engineered to prevent activation of other components of the immune system, and, as a result, unintended immune response to IMVT-1401 is not expected. Specifically, well-characterized and validated mutations introduced into the fragment crystallizable domain of IMVT-1401 have reduced its ability to cause ADCC and CDC.

FcRn, IgG Antibody Recycling and IMVT-1401 Mechanism of Action

The neonatal fragment crystallizable receptor is a cellular receptor that can bind IgG antibodies and guide their transport through cells. FcRn is named as such given its critical role in transferring maternal IgG antibodies contained in breast milk across the gut into the neonate’s bloodstream, providing passive immunity until such time as the child is sufficiently mature to produce its own antibodies. FcRn is also involved in the transfer of maternal IgG antibodies across the placenta in the developing fetus.

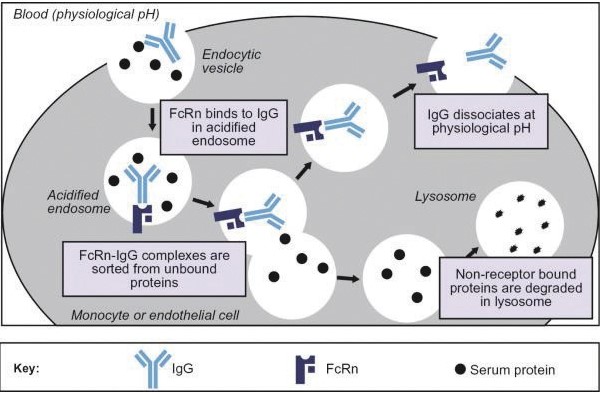

In adults, FcRn is the primary protein responsible for preventing the degradation of IgG antibodies and albumin, the most abundant protein found in the blood. IgG antibodies are constantly being removed from circulation and internalized in cellular organelles called endosomes. The role of FcRn is to bind to the IgG antibodies under the more acidic conditions of the endosome and transport them to the cell surface, where the neutral pH causes them to be released back into circulation. This FcRn mechanism of action and IgG antibody recycling is depicted in the graphic below.

FcRn and IgG Antibody Recycling

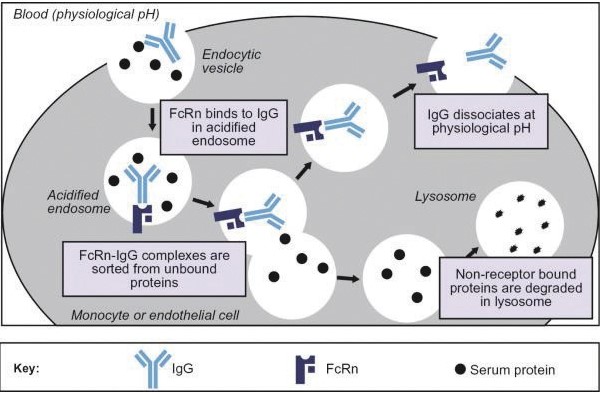

Our product candidate, IMVT-1401, is designed to block the recycling of IgG antibodies, resulting in their removal from circulation. IMVT-1401 binds to FcRn, blocking the ability of FcRn to bind to IgG antibodies under the more acidic conditions of the endosome. As a result, the bound IMVT-1401 and FcRn are transported to the cell surface, where FcRn is prevented from further recycling IgG antibodies as IMVT-1401 remains bound to FcRn even in the pH neutral environment outside the endosome. Meanwhile, the unbound IgG antibodies are degraded in the lysosome rather than being transported by FcRn for release back into circulation. This IMVT-1401 mechanism of action is depicted in the graphic below.

IMVT-1401’s Mechanism of Action

Clinical Development of IMVT-1401

We are developing IMVT-1401 as a fixed-dose subcutaneous injection for a variety of IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases, and have focused our initial development efforts on the treatment of MG, WAIHA and TED . We are also pursuing a series of other indications.

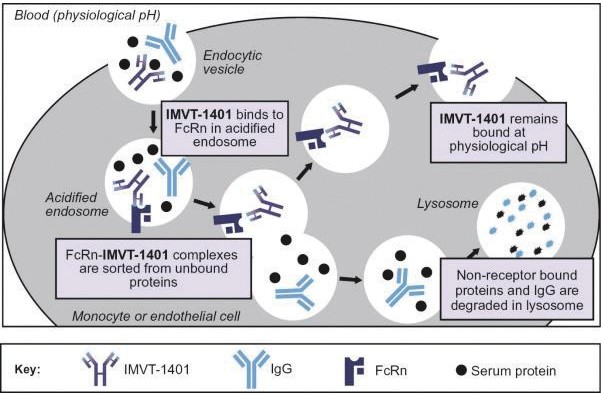

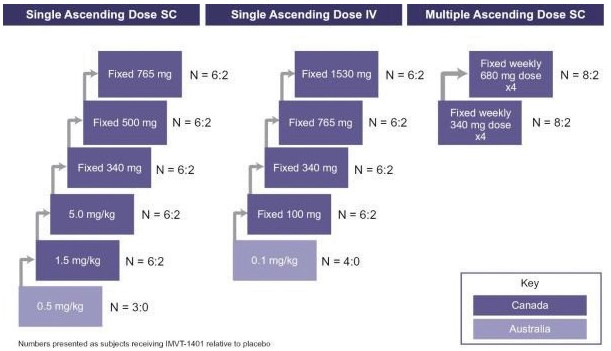

Phase 1 Clinical Trials of IMVT-1401 in Healthy Volunteers

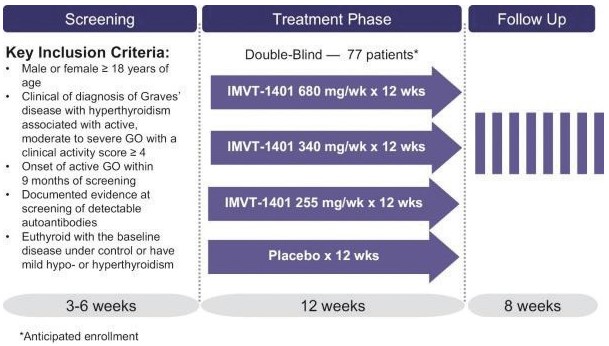

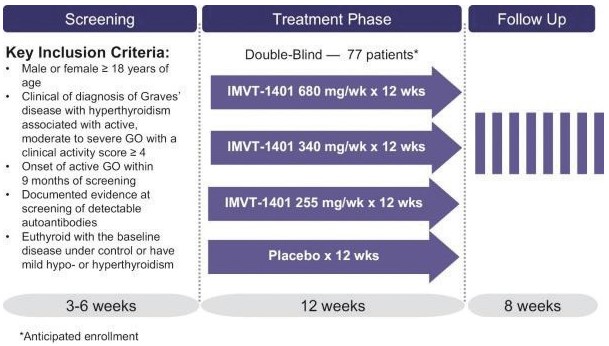

We have completed a multi-part, placebo-controlled Phase 1 clinical trial involving 99 healthy volunteers in Australia and Canada, administering IMVT-1401 both as an intravenous infusion and as a subcutaneous injection. In this trial, 77 subjects received at least one dose of IMVT-1401 and 22 subjects received placebo. The results of our Phase 1 trial are presented below:

Trial Design of Multi-Part Phase 1 Clinical Trial of IMVT-1401

Australian Trial data is not presented

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

The PK and PD (including serum concentrations of total IgG, albumin, and lipids) of IMVT-1401 were evaluated in healthy subjects in our Phase 1 clinical trial and Phase 1 Injection Site Study, and in patients with MG, TED and WAIHA in our ASCEND MG, ASCEND GO-1, ASCEND GO-2 and ASCEND WAIHA trials. To date, single doses of IMVT-1401 ranged from 100 mg to 1530 mg IV and 1.5 mg/kg to 765 mg SC and were administered to healthy subjects. Multiple doses of 255 mg, 340 mg and 680 mg SC QW have been studied in healthy subjects (up to 4 weeks of dosing) and patients with TED, MG or WAIHA (up to 12 weeks of dosing).

Pharmacokinetics

IMVT-1401 exhibited a non-linear PK profile which was typical of that characterized by target-mediated drug disposition ("TMDD"). The elimination of IMVT-1401 can be divided into three phases according to the concentrations. The first phase shows linear elimination; when drug concentrations are high enough to saturate targets, drug elimination is governed by linear non-target-related routes, together with a fixed rate of target-mediated elimination, which is negligible in this phase. At the second phase, the drug concentrations become lower, the targets are not all saturated and both non-target-mediated and target-mediated elimination routes are important, resulting in nonlinear PK. At the last phase, the drug concentrations are so low that targets are not saturated, the target mediated elimination becomes the main route of elimination, and the PK becomes linear again. The drug concentrations achieved after 680 mg SC QW dose were mainly in the linear elimination phase of the PK profile, may maintain target saturation during the dosing intervals for most of the subjects. However, the drug concentrations achieved after the 340 mg or 255 mg SC QW dose may not always maintain target saturation during the dosing intervals for majority of the subjects.

Pharmacodynamics

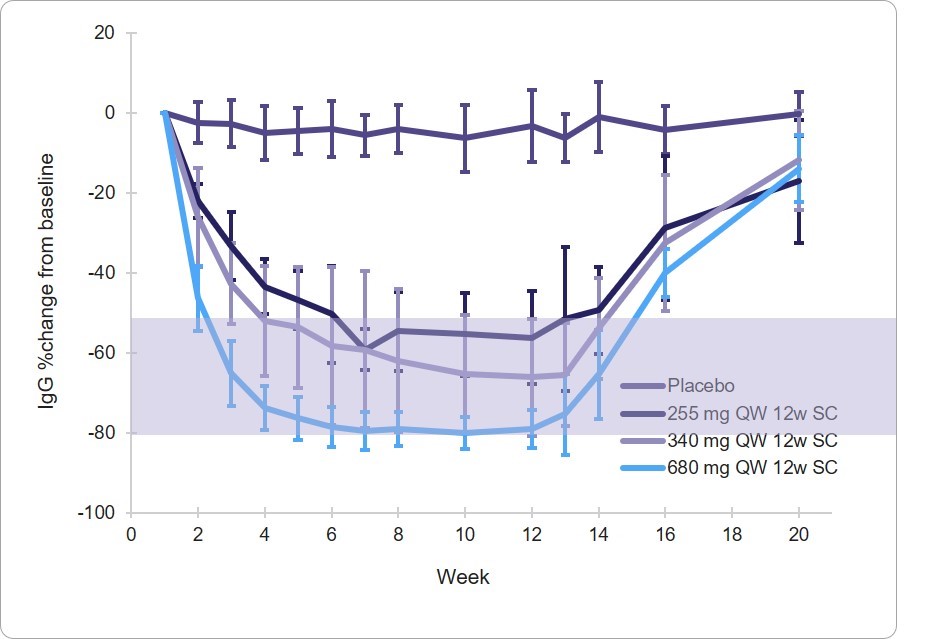

Currently, ASCEND GO-2 in TED is the largest study (total of 65 subjects, including 18 subjects on placebo) evaluated placebo and 3-dose levels of IMVT-1401 at 255 mg, 340 mg and 680 mg administered SC weekly for 12 weeks (“QW*12”). The preliminary PD results of total IgG by time and treatment group is presented in Figure 1. The baseline serum levels of total IgG, albumin, LDL, and HDL were comparable across all treatment groups. After active treatment, the levels of total IgG and albumin started to decrease, but the levels of LDL and HDL started to increase; both the rate and extent of reductions in total IgG and albumin or elevations of LDL and HDL were dose dependent. After 255 mg, 340 mg or 680 mg QW*12, the median Emax of total IgG reduction was 62%, 69% or 80%, respectively. For Groups 255 mg and 340 mg, total IgG levels continued to decrease as of week 12 (the last injection). For Group 680 mg, total IgG reached maximum reduction around week 7, and maintained in a plateau-like manner between weeks 7 to 12. The median Emax of albumin reduction was 16%, 26% or 40% for the 255 mg, 340 mg or 680 mg QW*12 doses, respectively. For Groups 340 mg and 680 mg, albumin levels continued to decrease as of week 12 (the last injection). For Group 255 mg, albumin reduction reached maximum around week 8, and maintained in a plateau-like manner between weeks 8 to 12. After 255 mg, 340 mg or 680 mg QW*12, the median elevation at Week 12 was 15%, 37% or 52%, respectively for LDL, and 14%, 10% or 25%, respectively for HDL. For all three active dose groups, the levels of total IgG, albumin, LDL and HDL returned to baseline within 8 weeks after the last dose of the 12-week treatment.

Figure 1 Mean (±SD) Percentage Change from Baseline of Serum Concentrations of Total IgG in Subjects in ASCEND GO-2 (Preliminary Results)

The relationships of the PD effects in total LDL vs. albumin indicate that the time course and extent of LDL elevations were highly correlated with albumin reductions. The reductions in both IgG and albumin were also highly correlated, with a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.793. It was also noted that the lipid elevations were not correlated with changes in thyroid hormone levels (no correlations to changes in T3, T4 or TSH was observed).

Within the dose range studied, the rate and extent of total IgG reductions, albumin reductions and lipid elevations were dose dependent across different populations and the shoulder region of the dose-response curve for total IgG reductions was covered and observed. However, the shoulder region of the dose-response curve for albumin reductions or lipid elevations was not clearly observed. The extent of PD response was much larger in reductions of total IgG than reductions of albumin or elevations of lipids.

Comprehensive understanding of the PK and PD characteristics of IMVT-1401 has enabled creation of robust mathematical models to support the selection of future dosing regimens. The discordance between the PK/PD response relationship for IgG and that of albumin or LDL suggests options for dosing regimens that provide potentially effective reductions in total IgG (and pathologic autoantibodies) while minimizing effects on albumin and LDL levels. Optimized dosing regimens, if shown to be effective, could improve the risk/benefit profile of IMVT-1401 while the ease of administration of our current formulation could enhance the overall patient experience.

Safety Data

We conducted, from February 2021 through May 2021, a program-wide data review, including safety data review, with input from external scientific and medical experts. The safety data review for each of the studies is described below.

In our multi-part, placebo-controlled Phase 1 clinical trial, IMVT-1401 was observed to be generally well-tolerated with no Grade 3 or Grade 4 treatment-emergent AEs and no discontinuations due to AEs. The most commonly reported AEs were mild erythema and swelling at the injection site, which typically resolved within hours and had a similar incidence between subjects receiving IMVT-1401 and placebo. These reactions at the injection site were not considered dose-related and did not increase with multiple administrations of IMVT-1401 in the multiple-dose cohorts. As previously disclosed, two serious AEs were reported, both of which were assessed as unrelated to IMVT-1401 by the study investigator. There were no treatment-related serious AEs reported.

A summary of the most commonly reported AEs, defined as the AE reported occurred in more than one subject, is set forth in the table below:

Most Common Adverse Events Reported in Phase 1 Clinical Trial of IMVT-1401

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Single Ascending Dose | | | | | | |

| | Intravenous Infusion | | Subcutaneous Injection | | Multiple Ascending Dose

Subcutaneous Injection |

| Number of Subjects | | 0.1

MG/

KG

N=4 | | 100

MG

N=6 | | 340

MG

N=6 | | 765

MG

N=6 | | 1530

MG

N=6 | | Placebo

N=8 | | 0.5

MG/KG

N=3 | | 1.5

MG/KG

N=6 | | 5

MG/KG

N=6 | | 340

MG

N=6 | | 500

MG

N=6 | | 765

MG

N=6 | | Placebo

N=10 | | 340

MG

N=8 | | 680

MG

N=8 | | Placebo

N=4 |

| MedDRA Preferred Term | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Abdominal pain | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | |

| Abdominal pain upper | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2 | | 1 | | | | |

| Abnormal sensation in eye | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Back pain | | | | | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | 1 | | | | |

| Constipation | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | |

| Cough | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | 2 | | | | | | |

| Diarrhea | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | |

| Dizziness | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | 1 |

| Dry skin | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | |

| Erythema | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | |

| Fatigue | | 1 | | | | | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | |

| Headache | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 | | | | | | 1 | | 1 | | 4 | | 1 | | | | 1 | | 2 | | | | |

| Injection site erythema | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 5 | | 1 | | 5 | | 6 | | 7 | | 8 | | 7 | | 4 |

| Injection site pain | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | 2 | | | | 1 |

| Injection site swelling | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 3 | | | | 2 | | 4 | | 3 | | 7 | | 6 | | 2 |

| Insomnia | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | 4 | | | | |

| Myalgia | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | 1 | | |

| Nasal congestion | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | 1 | | | | |

| Nausea | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | 1 | | | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | 1 |

| Ocular hyperaemia | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 2 | | |

| Oropharyngeal pain | | 1 | | | | | | 1 | | 2 | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | 2 | | | | |

| Pain in extremity | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | |

| Procedural complication | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Procedural dizziness | | | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | |

| Pyrexia | | | | | | 1 | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Rash | | | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | 1 | | |

| Rhinorrhoea | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | 2 | | | | | | |

| Sinusitis | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | |

| Somnolence | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 | | | | | | | | 3 | | | | 1 | | 1 | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | |

| Vision blurred | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | | |

In November 2018, one serious AE (malpighian carcinoma) occurred in a 51-year-old subject who had received a single 765 mg subcutaneous administration of IMVT-1401. Fifty-five days after study drug administration, the subject presented to his personal physician with a left-sided neck mass. Biopsy results determined the mass to be a poorly differentiated malpighian carcinoma, which was assessed as unrelated to IMVT-1401 by the study investigator. In February 2019, a 25-year-old subject who received a single dose 1530 mg of IMVT-1401 by intravenous infusion presented five days later with uncomplicated acute appendicitis and the presence of an appendiceal stone. The subject underwent laparoscopic appendectomy and recovered with an uneventful post-operative course. The event was considered unrelated to study drug by the study investigator.

Dose-dependent and reversible albumin reductions were observed in the single-ascending and multiple-ascending dose cohorts. In the 680 mg multiple-ascending dose cohort, most subjects appeared to reach nadir before administration of the final dose. Mean reduction in albumin levels at day 28 were 20% in the 340 mg multiple-dose cohort, and 31% in the 680 mg multiple-dose cohort. For subjects in the 340 mg and 680 mg cohorts, the mean albumin levels at day 28 were 37.5 g/L and 32.4 g/L, respectively (normal range 36-51 g/L). These reductions were not associated with any AEs or clinical symptoms and did not lead to any study discontinuations.

Our Phase 1 Injection Site study, a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study to characterize the PK, PD, safety and tolerability of IMVT-1401 was administered as single subcutaneous doses in three different injection sites in healthy participants (N = 21). In this trial, IMVT-1401 was generally well tolerated with no serious AEs reported and there were no discontinuations due to AEs. All AEs were assessed to be unrelated to IMVT-1401 by the study investigator. Mild headache was reported in 33% of the overall group as compared with 25% of the placebo group.

In our ASCEND GO-1 clinical trial, where seven participants completed the treatment period of the study and five of those participants completed the follow-up, off treatment period (the two discontinuations were not related to the study), the safety and tolerability profile observed was consistent with the Phase 1 clinical trials. In this trial, no serious AEs were observed and there were no discontinuations due to AEs. IMVT-1401 was generally well-tolerated, with the reported AEs, ranging from mild to moderate, being increase in weight, cough, fatigue, palpitations, light-headedness, and low blood pressure. One participant had a pre-existing condition of hypertension with borderline low platelets at baseline and a low platelet count after week 18.

In our ASCEND MG clinical trial, which included five participants in the 340 mg dose group, six participants in the 680 mg dose group and six participants in the placebo group, two serious AEs were reported but determined to be unrelated to IMVT-1401 by the study investigator.

In our ASCEND GO-2 clinical trial, five out of 18 participants in the 680 mg dose group reported peripheral edema with no such events noted in the other treatment groups. The events were Grade 1 or 2 (on a scale of 1 to 5), were limited in duration, and did not require permanent discontinuation of study drug. There were no reported cardiac events and injection site erythema was more common in the treated groups as compared with the placebo group. In the 255 mg dose group, one AE, optic neuropathy, was considered serious due to hospitalization, but was ultimately determined to be unrelated to the study and the participant later recovered. Triglycerides were elevated in the 340 mg and 680 mg dose groups with two participants reporting levels above 300 mg/dL and <400 mg/dL. No other serious AEs were reported.

The ASCEND WAIHA study is an ongoing, open-label trial that has been evaluated with interim results. To date, one of the five trial subjects discontinued therapy after three 680 mg SC QW doses due to a serious AE (Immune thrombocytopenia). In January 2021, a 59-year-old subject presented for the scheduled week 4 study visit and reported gingival bleeding. The week 4 dose was not administered and laboratory results revealed decreases in platelet count. Platelet count was already at a decreased level at the time of enrollment. The subject received multiple platelet transfusions over the following few weeks. In February 2021, the AE was considered as resolved and no further transfusions were needed at that time. The study investigator considered the event related to aggravation of underlying disease activity (hemolytic anemia with immune thrombocytopenia) since the subject had decreased platelet counts at initial diagnosis; however, the study investigator stated that the investigational product’s role in causing or aggravating thrombocytopenia cannot be ruled out. The adverse event was determined to be possibly related to study drug.

As previously disclosed, lipid levels were not measured contemporaneously during these Phase 1, ASCEND MG and ASCEND GO-1 clinical trials of IMVT-1401. See “Recent Developments in Our Clinical Programs” for further discussion about lipid and albumin changes noted in our clinical trials.

Across all the clinical trial groups to date, we believe the safety profile of IMVT-1401 at the doses studied over a treatment interval of at least 12 weeks is acceptable and supports further development of these dosing regimens. As discussed in “Recent Developments in Our Clinical Programs,” dose-dependent decreases in albumin levels have been observed with IMVT-1401; however, these decreases were generally asymptomatic except for the potentially expected AE of peripheral edema which was observed only in the 680 mg dose group and resolved without permanent discontinuation of IMVT-1401. Dose-related increases in LDL and total cholesterol have also been observed with IMVT-1401. While increases in LDL of this magnitude over a 12-week treatment duration would not be expected to pose a safety concern for patients, the risk-benefit profile of long-term administration of IMVT-1401 will need to incorporate any unfavorable effects on lipid profiles. Future study designs which include long-term treatment extensions will employ extensive PK/PD modeling to select dosing regimens that optimize reductions in total IgG while minimizing effects on albumin and LDL. These protocols will likely include protocol-directed guidelines for the management of any observed lipid abnormalities. The indications that we are pursuing with IMVT-1401 are associated with substantial morbidity and currently available treatments (e.g., high dose intravenous methylprednisolone) associated with significant side effects. Therefore, we believe that, if IMVT-1401 is found to be effective in these diseases, the safety profile observed to date should result in a favorable risk-benefit profile for IMVT-1401.

No major adverse cardiovascular events have been reported to date in IMVT clinical trials.

Immunogenicity Data

The development of anti-drug antibodies (“ADA”) to IMVT-1401 was assessed across all dosed cohorts following single (IV and SC formulations) and multiple (SC formulation) administrations of IMVT-1401. Preliminary data show a similar frequency of treatment-emergent ADA development among subjects who received at least one administration of IMVT-1401 or placebo (8% and 6%, respectively). The antibody titers were low (≤ 1:16) consistent with the high sensitivity of the ADA assay. No subjects in either the 340 mg or 680 mg multiple ascending dose cohorts developed ADAs with treatment. ADAs will continue to be monitored throughout the development program.

IMVT-1401 for the Treatment of Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia Gravis Overview

MG is an autoimmune disorder associated with muscle weakness and fatigue. MG patients develop antibodies that lead to an immunological attack on critical signaling receptor proteins at the junction between nerve and muscle cells, thereby inhibiting the ability of nerves to communicate properly with muscles. This leads to muscle weakness intensified by activity, which can be localized to exclusively to ocular muscles or which can be more generalized throughout the body including muscles of respiration. Patients with localized ocular disease suffer from more limited symptoms, including droopy eyelids and blurred or double vision due to compromise of eye movements. The vast majority of MG patients demonstrate elevated serum levels of acetylcholine receptor (“AChR”) antibodies which disrupt signal transmission between nerve fibers and muscle fibers. These antibodies ultimately lead to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigue.